In advising projects both in art and tech, I often ask the founder or artist to consider the ephemerality of the project, for ambition and lifespan are not necessarily interchangeable or even co-dependent, even when sustainability is a key objective.

While permanence precludes time from the experience, temporariness makes us aware of time — it’s root word (tempus, in Latin). When there is a sense of an ending, time surfaces to our attention. We start asking questions: What was it good for anyway? Could we have done without all this while? What did it really add to our lives?

I ask artists and founders to imagine the end of their project not to encourage exit dreams of a sale or IPO (even if that helps with getting through the grind), but because it provides a vantage point to ask those questions, temporally inverted, and then approach them with more creative and energetic approaches: What is this good for? What about the project could we not do without? What can it really add to our lives?

It is highly unlikely that Twitter will actually shut down, though recent events have inspired obituaries in the form of drama-Tweeting. What was Twitter?

The sense of an ending has also spurred reflections on what the platform had done right, what it hasn’t done right enough, and the complexities that emerging social networking sites face. One of the perennial issues is content moderation.

Content moderation is inherently difficult because attitudes are less about words than the tone and context in which they are being said. Content moderation on online social platforms is inherently difficult because they are exactly the environments that flatten human behaviour into linear patterns churned out for consumption via recognition.

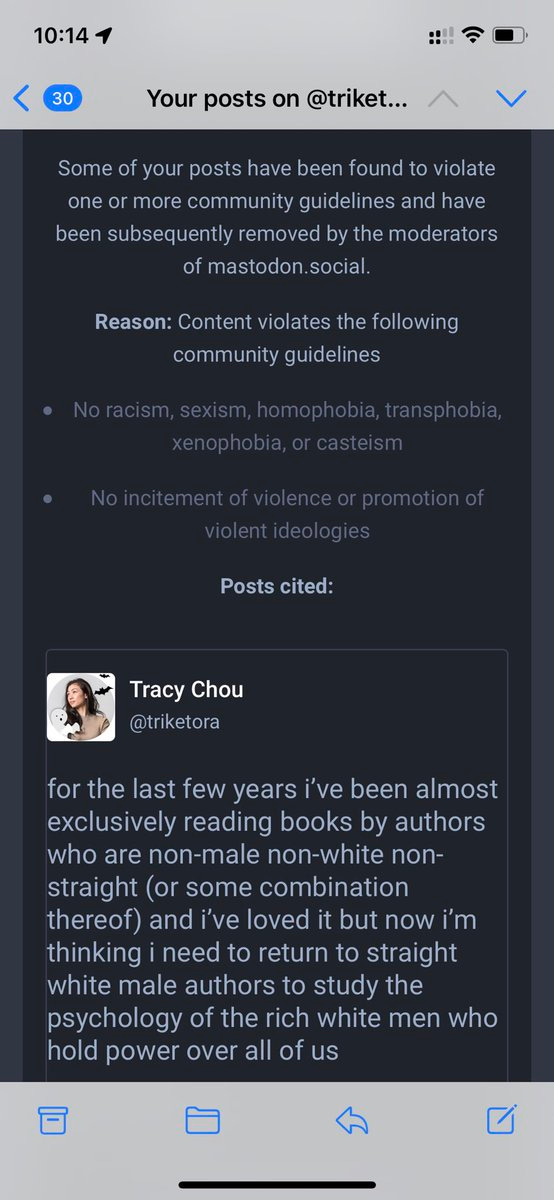

The problem is not that it is hard to identify undesirable and dangerous traits, but that we attach simplistic, outward-facing expressions to values on both sides of the fence, and rely on them to formulate, endorse and denounce identities. Reading books only by non-male non-white non-straight authors, or side-flexing that one does so (see Tweet below), does not make one egalitarian. It feels like we have flattened the ways that people (mis)treat each other through the funnels of social media into a binary lexicon we can’t see beyond or in between.

I saw this in play when I overheard a Gen Z boy telling off his same-age girlfriend, “You can Girlboss, you can Gatekeep, but you can’t Gaslight.”

I was astonished by how seamlessly and off-handedly this sentence was served, and also impressed by the phonology in that statement — it was almost poetic? Capitalising “G” was my initiative, but that was the cadence with which the words were spoken. The cadence that comes with the expected understanding of what values are indisputable.

So at least for the time being, some may find navigating the waters of decentralised social networks like Mastodon even more capricious than the old haunts.

Let’s not forget that media publishing (a term I prefer to content creation) was decentralised by web2 platforms. Media became something that was not only published and consumed through TV and radio broadcast or at the cinemas. Virtually anyone with an email account could publish in the format of their choice: audio, video, text, images of various dimensions. Yes, the storage, ownership and ultimately usage of the data that arose from activity on those platforms congregated in the hands of only very few people who profited from that power, but what decentralised infrastructure means for social relations is still a design challenge undergoing experimentation, one that requires understanding of why we seek and claim relationships in a space as public as the internet. The nuance will always lie in culture. I’ve written about the importance of sense-making through images in understanding technology, and we can apply that thinking here: how meaningful a social graph is to one’s reality is just as important as who owns it.

It’s been weeks since I overheard that Triple G-word lament, and my mind has been hung up on it. Maybe we — well-intentioned critics and theorists — got it all wrong. Maybe riffing off on how social media impacts the creation and representation of identity had us shooting arrows at a target with no centre in the first place. The over-reliance on trendy lingo of social networking sites had us confusing how we speak on but one platform with who we are. Verbs become nouns become titles. But human identities evolve, transpose, and become more or less pronounced in different environments. The internet itself has been a playground for people to explore multiple identities, but I would argue that a social media profile, along with the activities that it manifests, is closer to an archetypal image than an identity. Carl Jung believed there is no limit to the number of archetypes that may exist. How one behaves as an online avatar or profile is but one manifestation of an archetype, and there is usually plenty more that make up the prism of a person’s identity.

Every designer can tell you that there is always a temptation to take too seriously an aspect that wasn’t meant to hold that much weight. My provocation to detach the weight of something as irreducible as identity from social networking platforms comes in that vein. Chasing the dream of finding our identity online may have it captured instead.

The world is so big,

Jing

P.s. The trajectory/ies of social networks is something I’ve been researching for a while and I’d love to hear from you. Drop a comment or reply to this email if you have thoughts or experiences to share, I’d love to hear them.