The Synthesis of an Image

On locating the technology in the image, through the most iconic images of the glaringly familiar and the deepest unknowns.

Yesterday a total solar eclipse swept over North America, birthing a deluge of photographs of the phenomenon and its rippling shadows on Earth. Tomorrow marks five years since the first black hole photograph was published. This is an essay about technology being the image itself, not only the wares that make it.

⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜

Smell, fat, acid, heat

To illuminate non-human perception, the biophilosopher Jakob von Uexküll opened his 1934 book ‘A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with A Theory of Meaning’ depicting the life cycle of the tick, also known as the source of endless annoyance to campers, hikers, pet-owners, pets themselves, and quite possibly all other mammals in the wild of the planet’s land. Uexküll described the tick as a bandit both blind and deaf, expertly guided by its sense of touch and smell, in particular for butyric acid, a fatty acid given off by the skin glands of all mammals. The antihero of Uexküll’s story perceives, interprets, and acts on smell, heat, and surfaces. Its reaction to these stimuli is virtually what comprises its entire life cycle: the warm blood the tick diligently acquires is also its last meal, after which it detaches from its unassuming prey, lays eggs in the mass of several thousands, and dies. End of story.

To the human eye this member of the arachnid family is no larger than a sesame seed and whose sanguine feasting is, on most occasions, harmless. The dramaturgy of its lifespan, however, came in handy for von Uexküll to compare the approaches of the physiologist with that of the biologist. In honor of a life lived with such precision, patience and purpose, von Uexküll offers a question to illustrate the differing perspectives: “Is the tick a machine or a machine operator?”1

The physiologist, suggests Uexküll, whose world revolves around the human body and for whom every other is an external agent, sees the tick as a machine that acts on reflexes in accordance to receptors for certain external signals, namely butyric acid and heat. The biologist, however, would insist that those very signals have to be noticed in the first place in order to be acted upon by the tick, which thereby exhibits qualities of a machine operator throughout its modest but resolute life. Perception becomes the nuance that distinguishes a creature as a subject from a mere object. Uexküll’s contribution to biosemiotic theory was that each creature swims and acts in its idiosyncratic umwelt, the German word translating to ‘self-centered world.’2 In Uexküll’s theory of the umwelt, every individual creature perceives and acts on a phenomenal world of its own.

⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜

Bending light, bending photography

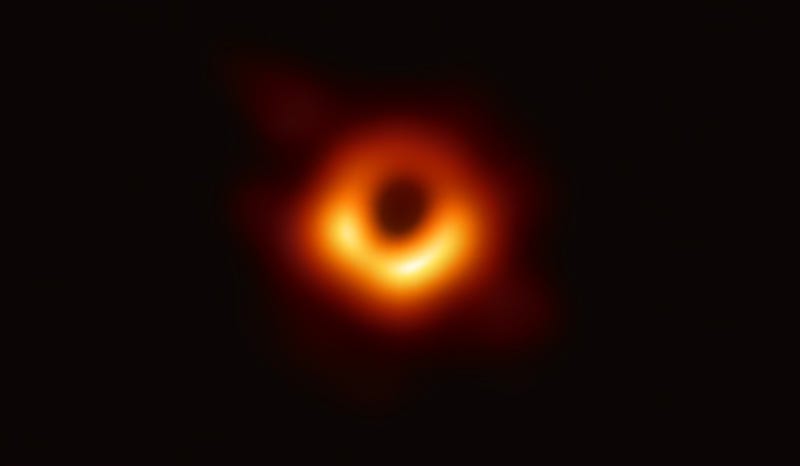

Images are everywhere and their meanings amorphous. But once in a thousand headlines, a single image would take the world over by storm. I was in Paris when the first photograph of a black hole was released to the world’s eye on April 10th, 2019. On the streets in the city of lights, kiosques were bursting with newspapers unified by the same photograph on every front page. Against the vast darkness of space, a fuzzy, fiery, reddish-orange glow caressed the circumference of a concise and dark silhouette cinematically positioned at the center of the image that would proliferate every media channel over the coming days. M87*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87 now had a face, and for the first time, a phenomenon which could previously only be detected by X-rays was now captured in an image. An image that required no words to achieve its iconic status, only an incomprehensible amount — five petabytes (or five million gigabytes) — of data.

At the core of the imaging process was the refinement of algorithms that allowed the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team to fill in the gaps between data collected from telescopes scattered at various locations across the Earth. In other words, the photograph was created not by way of a telescope zooming in on its subject 53 million light-years away, as one might imagine a photographer’s camera works, but by interpreting, reconstructing and assembling data from radio waves gathered by the network of telescopes.

The photograph of M87*, alongside other supermassive black holes the EHT has imaged in the years following, is observational proof of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. Perhaps lesser known as the geometric theory of gravity, Einstein’s field equations transcended Sir Isaac Newton’s definition of gravity by describing it not as a unilateral force that simply pulls the apple from tree to ground, but a consequence of a distortion in both space and time. Under Einstein’s theory, the fabric of space-time in which all matter exists is not only a metaphor but a tangible substance, as objects warp the ‘fabric’ that surrounds it, a warping that determines the objects’ movement in turn. As masses of the most extreme gravitational force, black holes cause the bending of every matter passing through their vicinity, up to a point. By definition, a black hole has not a surface but an event horizon: a boundary beyond which, as legend has it, not even light can escape.

The chances that the device on which you’re reading this essay is capable of snapping a photograph is likely entirely positive. The chances that it can do so in more than one orientation, possibly even simultaneously, is also quite likely. By now, our understanding of photography precedes the camera. When we pull up a smartphone to take aim, tap on a focal point, and hold still for a few seconds longer at nighttime to take a photo, we intuitively understand how photography works: the capture of light reflected off surfaces, photons of light rays translated to bits and bytes, or silver in the case of film. In taking photos on a daily basis we become familiar with parts and workings of the camera like shutter speed, aperture, depth of field, even if they require no more than a flicker of a finger to dial. To call the image of the M87* a photograph would therefore amount to a paradox in formalist terms as much as in mass-cultural perception in terms of photography as an image-making method. By displacing the camera as a categorical condition, however, we allow for a broader conceptual understanding of photography, and for photography as a model through which we perceive other technologies. In observing art of the 1970s, the art critic and theorist Rosalind Krauss proposed a way of thinking about art through photography as an “operative model for abstraction.”3 Defining photography by the “quality of transfer or trace,” the process that, like a weather vane’s registration of the wind, speaks of “a literal manifestation of presence.”4 Krauss drew attention to the photograph as an index and applied this approach to her analysis of art from abstract painting to sculpture and performance.

Krauss would continue to wield the technology of photography to analyze modernism at length — with the logic of the photograph-as-index in place of a camera in hand.

⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜

Geometries of coincidence

Prior to the M87* capture, there had been another photograph to shoot to iconic stardom, garnering the rare sort of universal wonder and emotion for not only defining an era marked by technological advancement, but a sense of emplacement in the vast cosmos.

It was on the fourth lap around the moon on the Apollo 8 mission that astronauts William Anders, Frank Borman and James Lovell were struck by the sight of Earth peering out of their vessel’s window. Pulling up a modified Hasselblad brought on mission to photograph the moon, Anders set the focus to infinity and snapped a shot of the bright blue globe hovering gracefully, miraculously, in the suspension of virtually nothing but space. The image is on all accounts a photograph taken through the traditional means of a film camera, but even then we can note the manipulations that resulted in the published ‘Earthrise’, as it was titled. The colors of the original image were saturated further after the Apollo 8 team delivered the film to NASA technicians, but more distinctly, Anders’ shot was rotated 95 degrees clockwise such that the Earth appears to rise over the moonscape. The decision to orient the image as such familiarized the image to one that we witness in our everyday: the sunrise. Although, by the time the photograph had been taken in 1968 more than three centuries of discovery and observation had given credence to the undisputed knowledge that all planets, stars and objects in space are in relative motion, and any observable plane from which one of them would appear to ‘rise’ is but a geometry of coincidence.

Accompanying ‘Earthrise’ on the front page of the New York Times on Christmas Day that year was an essay by the poet Archibald MacLeish describing the photograph’s significance in allowing us “to see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats.”5 By the time the photograph had made its appearances in stamps and magazine covers, it was clear that the profound torrents of spiritual and emotional awakenings it stirred were due to the imagery of the Earth as our home, singular, fragile, and beautiful. The significance of ‘Earthrise’ as an image, as in Krauss’ indexical operation to the reality of an exact moment in space and time, however, did not slip past Luigi Ghirri, a late Italian artist who saw photography not only as a method but also a subject that allows us to step away from the constraints of symbolism. On ‘Earthrise’, he wrote, “It was not only the image of the entire world, but the only image that contained all other images of the world: graffiti, frescoes, paintings, writings, photographs, books, films. It was at once the representation of the world and all representations of the world.”6

In phenomenon and in composition, “Earthrise” and the EHT photograph are polar opposites. One is the all-encompassing image of the world we live in, a convex mirror in which all that we know is contained; the other a picture of unknown, dense and infinite, a portrait of a space and time that even when imaged remains unimaginable.

The afternoon of April 10th, 2019, the day that the M87* photograph was released, I visited Jeu de Paume, where a retrospective of Ghirri’s work was being exhibited.

Shooting exclusively with color film in the 1970s and 1980s, Ghirri lamented the European bias towards black-and-white photography and other reliance on stylization. Instead, he cast his lens on objects and other images such as advertising billboards, posters and postcards, which were regarded in bad taste, as kitsch, but nonetheless inevitable as surface for the human gaze. ’Kodachrome’ (1970-1978), Ghirri’s most wide-spanning series named after the brand of film — Kodak — often utilized the aspect ratio of the 35mm film to expose the photographer’s intervention. The spacious galleries of the museum seemed even more generous containing series after series of Ghirri’s photographs, many of them postcard-sized themselves. For ‘Diaframma 11, 1/125, Luce Naturale’ (1970-1979), he photographed people caught in the act of looking. Through the viewfinder Ghirri would frame the image just so that tourists are caught gazing out not at an actual landscape but its representation, such as a map of the mountains, to create humorous, uncanny alignments of coincidence that foreground the saturation of signs and symbols that surround us, at once arbitrary and full of narrative possibilities.

I think of Ghirri’s practice as an answer to Susan Sontag’s call for “an ecology not only of real things but of images as well,” when she warned of the “aesthetic consumerism” that photography would premise.7 Her woes were of the ability to reproduce images of an existent experience at such immediacy and ease that the human eye would be anesthetized, and the only antidote was for the “real world to include the one of images.”8 As I exited the museum and re-immersed in the real world of the streets and social media, where the EHT photograph would enjoy ubiquity over the next three or four days, it became clear that images are part of our phenomenal worlds just as ‘real things’ are. Images, too, form our umwelt.

⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜

Dots in the icons

Ghirri’s work is a reminder that the limits of the photographic image hinges not only on what eludes representation because it is too far, too big or too small to be captured by the apparatus, but more likely on decision of the image-maker. Images, whether created by the hobbyist’s point-and-shoot camera or through engineered methods such as photogrammetry or advanced data processing techniques, are surfaces of cultural production and predilection.

But when we consider the wider production of images including the images produced neither by nor for the human gaze but machine systems, images do more than represent. In the early 2000s the filmmaker, artist and writer Harun Farocki theorized the shift in the role of the image from representational to operational by analyzing images that were captured and created for the ‘eyes’ of machines in tools of measurement and surveillance, especially deployed for factory or military purposes. These ‘operative images’, as Farocki identified them, are “made neither to entertain nor to inform”, and “do not represent an object, but rather are part of an operation.”9 As images generated by programs built on artificial intelligence begin to flood our visual culture, Farocki’s studies on the existence, transformation and utility — in other words, the life cycles — of non-representational images becomes vital as both (co-)maker and viewer of the AI-generated image remain largely in the dark with regards to the sets of other images that are nonetheless dissected, assembled and reformed in the making of a novel one.

In the essay ‘Reality Would Have To Begin,' Farocki shares Krauss’ sentiment that photography is an analog technology because a photographic image “is an impression (of reality) at a distance, made with the help of optics and chemistry.”10 He goes on, however, to note media philosopher Vilém Flusser in pointing out that digital technology was also already located in photography because the photographic image is built out of dots of information which the human eye synthesizes into an image. It was out of this dual-quality of photography that Farocki predicted almost two decades before DALL-E opened to public access that because machines have been dividing images into discrete units without the need for consciousness or experience of the form, “images without originals become possible and, hence, generated images.”11

If AI-generated images causes fear amidst fascination, it is in large part because they reveal the assumption of veracity through images, tearing apart the notion that pictures are proof (or, in today’s parlance, ‘pics or it didn’t happen’). To make sense of the image at the time of post-modernism’s peak, we have to first understand the ways that images have formed our umwelt, as sign, signal, sound and noise, just as the biologist in Uexküll’s tale makes sense of the tick. By unraveling the processes that gave us the most iconic images of the glaringly familiar and the deepest unknown, we are able to understand photography’s digital-analog dichotomy, as well as what historians of science have debated for decades: the degree to which scientific judgment, idealized imagery and technical affordances each layer into images that scientists put out for the rest of us to see the world. Borrowing Flusser’s framework for photography, all images, regardless of the apparatus used in their creation, are as generative as they are analog. We may be better equipped to understand the current paradigm shift in our media ecology by locating the technology not only in the software but also in the image.

⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜ ⏝ ⏜

Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with A Theory of Meaning (University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 45.

Kalevi Kull, “Umwelt and Modeling,” The Routledge Companion to Semiotics, ed. Paul Cobley (London: Routledge, 2010), 48-49, ISBN 978-0-415-44072-1.

Krauss, Rosalind, “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America. Part 2,” October 4 (1977): 58–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/778480.

Krauss, “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America. Part 2,” 59.

Archibald MacLeish, “Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold,” New York Times, December 25, 1968, 1.

Luigi Ghirri, Kodachrome: Introduction (Modena, Punto e Virgola, 1978), 1.

Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 16-19.

Sontag, On Photography, 141.

Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public, no. 29 (January 2004), 18.

Harun Farocki, "Reality Would Have to Begin” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sight-Lines, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 197.

Farocki, "Reality Would Have to Begin,” 197.